Something that comes up a lot when talking about investing is diversification. One simple view of this is “don’t put all your eggs in one basket”. However, there is a lot more to diversification than simply playing it safe or hedging your bets. Behavioural finance studies typically highlight that emotional investing can often derail well thought out, defined investment objectives. Diversification is one of the most important concepts in investing but it only works when investors stay disciplined and don’t make reactive bets because of a fear of missing out (FOMO).

The main objective of diversifying your portfolio is usually not to maximise its performance but to insure you against the big potential losses that a concentration in one specific sector or asset class can bring. Diversification of asset classes is often a keystone for robust investment portfolio. This most typically takes the form of a general negative correlation between bonds and equities.

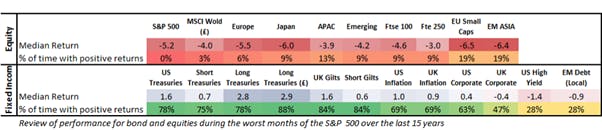

As can be seen on the table below, during the worst negative months for the S&P 500, US treasuries rose 78% of the time. Taking into account the currency impact for UK investors when converting to pounds, those bonds would have risen a stunning 88% of the time while equities were down. ‘Gilts’ (UK bonds) would have risen 84% of the time.

Source: Nutmeg/MacroBond

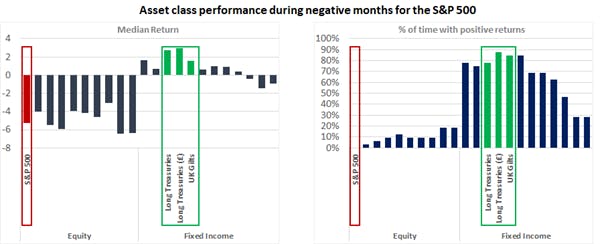

The bar chart below also captures this relationship over the last 15 years. As you can see on the left, when equities are in the negative, bonds are in the positive; likewise, on the right we can see that almost 90% of the time that equities are not returning, bonds are returning:

Source: Nutmeg/MacroBond

Diversifying within the same asset class

The world of market economics cannot really be simplified into “when equities go down bonds go up and vice versa”. Of almost equal important is the use of diversification within respective asset classes. While more nuanced than multi-asset investing, diversifying your holdings within one asset class can help minimise risk. A portfolio of equity well diversified by region, market cap and style will offer more diversification than one with only a single country or with only a limited number of stocks.

Diversification vs FOMO

The concept of diversification described seems rational and straightforward, but practice does not always mirror theory. When markets are moving and good times stories abound, it is easy to be dragged in by the fear of missing out (FOMO) on a transient opportunity. However, unlike the solid logic behind diversification, FOMO is actually often the result of different interlinked causes such as false beliefs, trend bias, greed and social pressure. It’s worth detailing these factors here to illustrate how they can impact your ability to maintain diversification when investing.

Trend bias

Trend bias is inherent to most human beings. The human brain tends to believe that what was true for an extended period of time, will continue to be true. This has logic – but not certainty and you should never use the former without remembering the latter.

Looking at equities over the last thirty years, one can identify a major trend per decade:

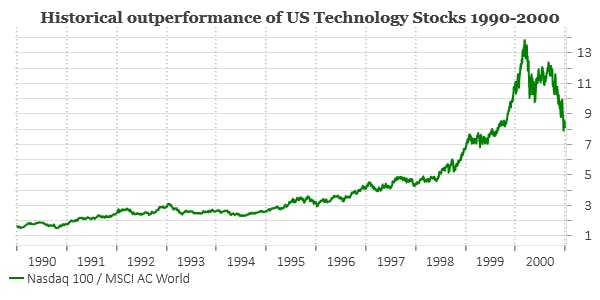

First, the 90s were dominated by the outperformance of US technology stocks. The chart below highlights how, between 1990 and 1999, technology stocks gave a long-term positive trend vs. the rest of the world’s equity stocks. The Nasdaq consistently outperformed over the period with a particularly strong trend toward the end of the period.

Source: MacroBond (X axis: total return)

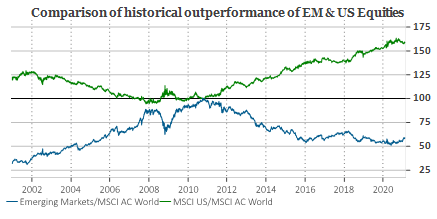

During the 2000s and up to the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2008, it was all about emerging markets. Up to that point, emerging market stocks consistently outperformed the rest of the world as can be seen on the chart below.

Source: MacroBond (X axis: total return)

Emerging stocks, which were often reduced to the ‘BRICS’ (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa), became a significant part of many investors’ portfolios. However, as we can see above, the next decade (2010 to 2020) was much less appealing for the relative performance of emerging countries with most of the excess performance actually disappearing. Conversely, the US equity market shows almost the opposite profile with a long period of underperformance between 2001 and 2008, followed by a period of consistent outperformance between 2010 to 2020.

With trend bias, it is of course tempting to believe that the dominance of US equity markets over the last 10 years will simply continue. This view applies to the same trend bias logic that many investors would have had in 2010 about emerging markets – but if they were too overweight in those markets and not diversified enough into US equities, they would have lost out. Looking at the total 20 years covered by the chart we can see diversification is good way to help mitigate the drops in one market and to benefit from the rises in another.

Looking forward, trend bias would suggest a continuation of the rise in US stocks between 2021 and 2030 but, for now, with no crystal ball, being diversified remains the best obvious choice an investor can make.

Greed

Greed has a lot in common with trend bias but arguably has higher levels of irrationality. In investment terms we can identify it as when an investor loses sight of their rational objectives and starts to make large aggressive bets in the market. By doing this, they forfeit the basic risk framework they used to define their portfolio and investment philosophy – potentially taking more risk and forgetting the purpose and reasoning behind the portfolio in the first place.

One current example could be to put all investments in US equity or in technology stocks based on the trend over the last 10 years – or even just the last 10 months. While the outperformance of those stocks can of course last for an extended period of time, it is by no means certain, so keeping a good level of diversification is crucial to achieving one’s objective. If you had made this jump, putting your whole portfolio into the NASDAQ tech index, at the beginning of March 2021, you might well have lost 10% of its total value.

As we can see from the same article, had you been diversified within your equity asset class (holding other indexes), you could have limited your NASDAQ losses, while making gains on your Dow Jones holdings.

Social pressure

Social pressure is a more qualitative influencer. This is often the anecdotal small cap stock tip given by a successful acquaintance at a dinner; or from the son of a friend who made a fortune investing in cryptocurrencies. We often hear others talking about their successful bets on a specific asset class or a single financial instrument. What we don’t hear about is how, with every single position, even the most successful ones, there is often a considerable level of risk taken, especially when it is a highly concentrated bet. People also very rarely talk about their failures and, while the media love a golden ticket story, they never report on the millions of investors quietly growing their portfolios over time without taking hundred-to-one shots.

While there are always winning asset classes somewhere, diversification is really the ability to stick to the level of risk that one can afford. Missing out on the short-term excitement is a price most would gladly pay for a comfortable retirement income.

A cautionary tale: the Stan Druckenmiller story

Even for the top investors, it is often difficult to avoid succumbing to trend bias, greed and social pressure. The example of the legendary investor Stan Druckenmiller is particularly telling. For more than a decade Stan Druckenmiller ran the famous Soros Quantum fund; he was the main architect of the famous bet that broke the Bank of England in 1992.

Toward the middle of 1999, Druckenmiller was largely avoiding US technology stocks because, for him, their valuation was out of sync with reality. However, the Soros Quantum fund then began to underperform. Druckenmiller decided to reverse his bet against US tech and, encouraged by recently hired tech-savvy investment analysts, he began to invest in US tech very heavily, despite this large bet being contrary to his principle of sound valuation.

The performance of his fund went from -11% to end 1999 with a performance of more than +35%. Despite George Soros’s opposition, Druckenmiller then doubled up on this bet in early 2000: dramatically increasing the fund’s exposure to US tech – and reducing his overall diversification.

The market reversed sharply in March 2000 and within six weeks Stanley Druckenmiller was out of a job at the Soros Quantum fund; his FOMO and inability to maintain diversification ultimately cost the fund over billion. The fund decided to restructure and took the loss of most of this bet.

So, even the most high-profile investors have shown that keeping a high level of diversification can be difficult, especially when some areas of the market are showing high levels of exuberance. As rightly said by Harry Markovitz: “diversification is the only free lunch in investing”. Equally apt is the advice to keep your head when all around you are losing theirs.

References:

“How the Soros Funds Lost Game Of Chicken Against Tech Stocks”

“Diversification is the only free lunch in investing” is attributed to Harry Markovitz, Nobel Prize laureate and Pioneer of the Modern Portfolio Theory

As with all investing, your capital is at risk. The value of your portfolio with Nutmeg can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you invest. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. Forecasts are also not a reliable indicator of future performance.