Geopolitical, social and ecological ruptures have become front of mind for politicians, businesses, the media and financial markets over the last few years. Long–term investing can often take for granted the continuity of prevailing global systems; specifically, the reliance of finance on natural resource access, established supply chains, technological capabilities and political stability. In this special Nutmeg report, we discuss the possibility of global financial disruption as the result of a developing rivalry between the United States and the People’s Republic of China.

This rivalry is now formative in the commercial, intellectual, political and military relationships between both states: raising the real possibility of decoupling. The new Biden administration is unlikely to change Washington’s assessment of underlying risks, identifying the need to balance, and possibly compete, with China as the default diplomatic position. The ongoing uncertainty as to what form that balancing might take, raises two key questions for our investors:

“Does Nutmeg expect the world to decouple?””

and

“Are the ‘tried and tested’ investment rules forged in the 1990s and 2000s still relevant in a very different geopolitical backdrop?”

We address these questions here and conclude that both the US and China retain vested interests in finding an accommodation that will allow their different civil and economic systems to coexist.

Reasons to think decoupling will be limited

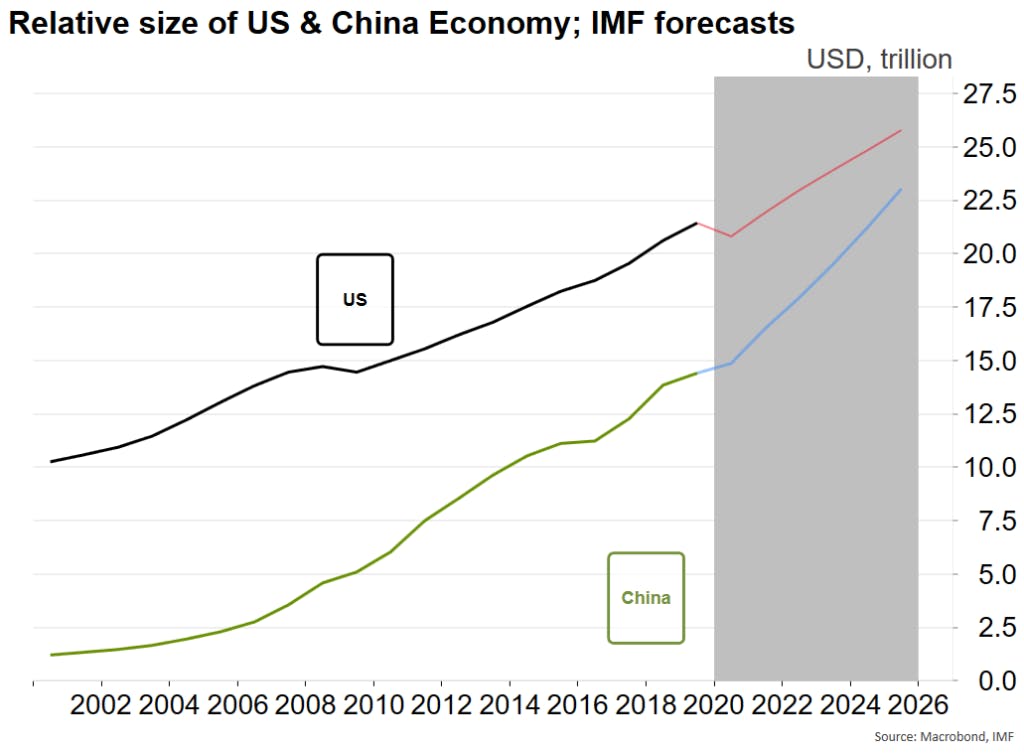

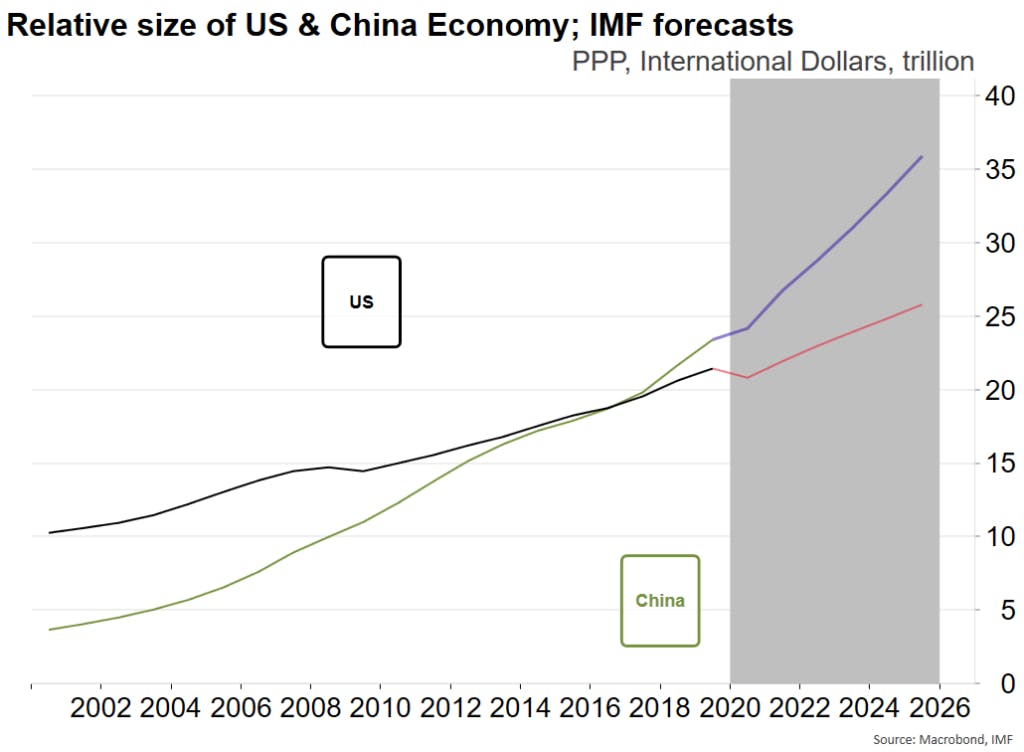

In the last two decades China has surpassed Japan as the centre of economic power in Asia. China’s economic success has been accompanied by the reassertion of its political, military, and strategic role: a challenge to the US which has been the region’s policeman since 1945. Furthermore, as shown below by Chart 1, China is projected to eclipse the size of the US economy. In purchasing-power-parity terms (PPP) this occurred around 2015 (Chart 1A).

Chart 1

Chart 1A

The narrative of a new bipolar world, with China replacing the Soviet Union as America’s counterweight, has heavily influenced global diplomacy since the Global Financial Crisis of 2007/8, which severely tested Western financial architecture, policy making, and multilateral solidarity. However, this narrative is not necessarily one of adversity and Nutmeg believe there are several reasons to expect the US and China to make accommodations for each other.

1. A well-used diplomatic framework exists

The US is backing away from its post WWII/Cold War role as global policeman as China’s regional role increases. However, geopolitical checks and balances can be maintained via the US’s bilateral and multilateral partnerships in the region (Japan, South Korea, India, Australia) and beyond (Africa). A recent example of such regional balancing, though without the US, is the signing, in November 2020, of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (‘RCEP’) trade deal between 15 countries including China, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand. The deal provides market access for China but it also provides channels of push-back and balance for all of the signatory regional economies who have a level of equivalence within the treaty as partners. Brookings research institute heralded “a triumph of ASEAN’s middle-power diplomacy” and credited the non-Chinese leadership that made the deal possible, predicting the addition of 00 billion to global incomes.

The world has already established an accommodation with China. Most of the world recognises Beijing’s One-China policy which interprets Taiwan as part of China, fudging the diplomatic issue of whether that “one” China is solely the “People’s Republic of China (‘PRC’)” ruled by the CCP, or also accommodates the “Republic of China (‘ROC’)” ruled by Taiwan’s democratically elected parliament. The US recognised the PRC in 1979, paving the way for China’s observer status on the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in the mid 1980’s and its ascension to the WTO in 2001. In the same year though, the US also passed the Taiwan Relations Act (TRA) to protect US commercial and security interests.

The TRA has as its explicit objective the preservation and enhancement of the human rights of the Taiwanese people; any threat to this is a threat to peace and security in the Western Pacific and of grave concern to the United States. The TRA looks to a united China, but only via a peaceful transition which respects Taiwanese citizen rights. This understanding continues to hold as its parameters are being tested. In January 2021, following the deployment of a US carrier-group to the region, Beijing made clear that independence “means war”; comments the US referred to as “unfortunate”, explaining that the Pentagon “sees no reason why tensions over Taiwan need to lead to anything like confrontation”.

2. The need to trade and balance of resources

The world is stitched together by the need to trade and the wealth that trade brings provides political legitimacy. Domestically, the Chinese Communist Party (‘CCP’) needs to ensure a viable economy maintains middle-class jobs and financial security. Closing off to international trade is a high-risk strategy in this regard. With a membership of 92 million – less than 7% of China’s population – the CCP is only ever “one revolution away” from losing its legitimacy in the minds of the broader Chinese population.

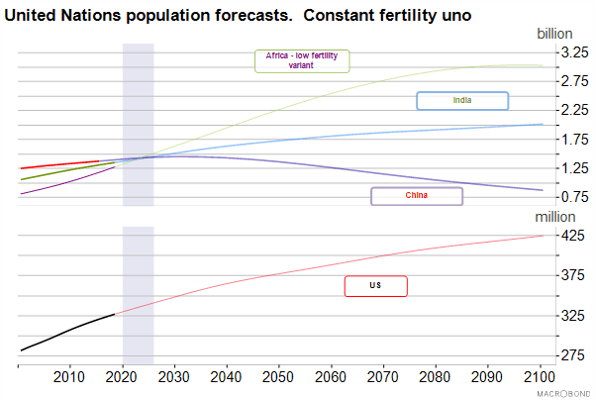

A sense of balance also persists as China’s rise can be replicated elsewhere as natural and human resources are spread globally, with no country in a total monopoly position. Other regions with large populations, such as India and Africa, have economic potential, and China is seeking to maintain and increase connectivity in both spaces. The respective populations of both India and Africa will surpass China’s in the next five years (See Chart 2).

Chart 2

As Chart 2 shows, in the next five years (shaded region), China’s population size gives way to Africa and India. China is notably a long-term player and these larger regions could become an economic threat if they exist in separate (decoupled) economic ecologies. While China has clearly sought economic and political influence in Asia and Africa, it is explicitly not a zero-sum approach.

Despite their differences with China, Western democracies retain trade in their DNA. ‘Twin-tracks’, whereby diplomatic pressure is applied while trade continues, are not new to global trade arrangements. Pressure and restrictions in areas such as arms, financial services and media does not preclude business elsewhere.

3. Mutual financial interests exist

China needs US banks operating inside its borders. Chinese banks are only just beginning to experience high levels of risk-rated lending. Credit and business risk analysis have not been at the forefront of Chinese lending practices as loan policies remain heavily influenced by government. China is looking to open -up its debt markets to foreign participation to help build necessary capital formation expertise. US banks, operating alongside Chinese banks, can improve capital allocation and train local staff to improve standards and knowledge.

In a similar vein, China’s drive for a bigger place in the global bond market requires adherence to the Paris Club rules which govern debt restructuring and debt wind-ups as well as the seniority of creditors. That will tend to limit the effectiveness of strategic lending – China’s historical approach – bringing it on to a par with the US and other Western creditors. Commercially, the US needs China because its companies want access to China’s growing middle classes. While the US government wants China to continue holding its 15% share of all Treasury Securities.

Recognising and dealing with mutual financial interests can pay dividends. For the US and other economies, active economic engagement is the best strategy for countering the existing problems of corporate espionage, theft of intellectual property and corporate corruption. A significant share of Chinese production is state owned, continued Western corporate involvement in China would inject a necessary dose of best-commercial-practice, as well as competition.

How investment rules are changing in the 2020s

It would be a mistake to use a simple decoupling vs non-decoupling dichotomy to form a future investment strategy. However, scrutiny of this juxtaposition does force us to analyse other variables – and how these might inform our investment outlook.

Even if the world does not decouple, financial environments are changing across emerging and developed markets (‘EM’ and ‘DM’). We are unlikely to have a re-run of the 2000s and the high-growth financial environment where the current crop of global investors learned their craft. There are a number of reasons for this which we list below. These are all important variables we will continue to observe.

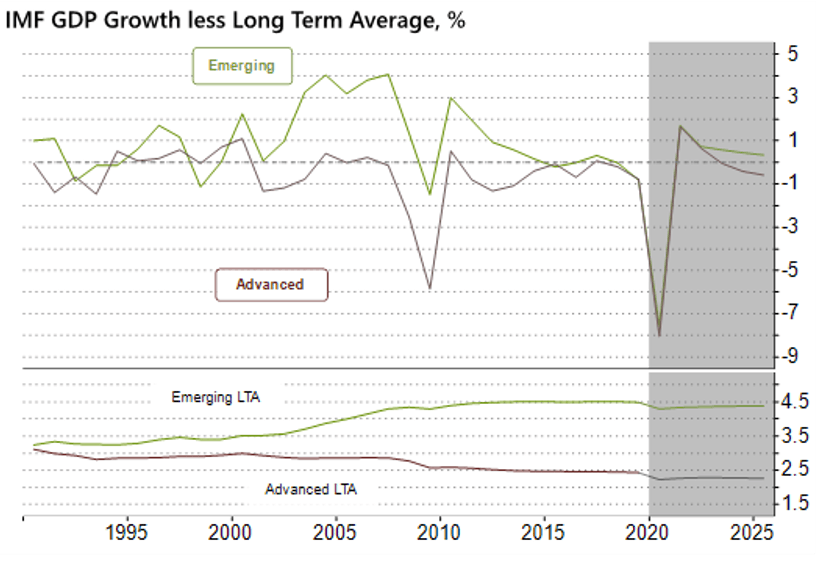

- EM growth faces major deceleration: The neutral level trend, neither bullish nor bearish, of EM GDP growth is likely well below 4.5% (Chart 3). China alone will struggle to average 4.5%, compared to the 10% levels reached in the late 1990s to early 2000s. The “catch-up” rationale of EM market investing has been curtailed, along with its expected excess return.

Chart 3

Source: IMF/Nutmeg

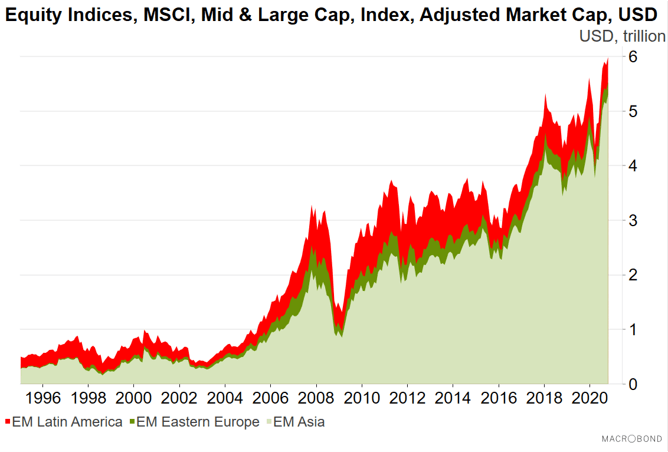

- EM indices have come to be dominated by Asia: Latin American (LatAm) markets are far less important than they were in the early 2000s (Chart 4). One impact of this is the changed relationship of the index through commodity prices and currency values. The Asian-EM region is a consumer of commodities, compared to LatAm, which is a producer. Another difference is the importance of technology stocks (a major growth sector) to the Asian-EM index.

Chart 4

- Decarbonisation is set to impact the EM space unevenly: The race for clean energy is a great leveller of opportunities for national economies. The major EM oil producers are Brazil, Mexico, Kazakhstan Russia, and the Middle East. We expect them to underperform Asian EM. Not only is Asia an oil consumer – benefitting from lower oil prices – but the region possesses the technology base to develop and sustain alternative energy.

- Digitisation, 3D printing and robotics make local production more viable for high wage, developed economies. Technology can supercharge catch–up growth for EM if populations are allowed to use it freely. This won’t always be the case in China but could well be the case in India and Africa, both of which have seen technological ‘leapfrogging’. This new trend will impact the overall EM risk premiums as well as the relative performance of EM

- The Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI) index continues to include allocations of China– listed ‘A category shares’. The previous rule was that China’s share of global listed equities would continue to grow and one day challenge the US. However, if the decoupling between the dual systems turns out to be too great, MSCI may be forced to reconsider its inclusion of China’s A-share market.

Conclusion

Nutmeg expects that US-China tensions will come to the fore again under a Democrat White House. There are clear ongoing issues around geopolitics and security, but we anticipate that the US and China will learn how to accommodate each other’s different types of governments.

China has a strong self-interest in staying engaged with the West even if it sees the loss of its historical supply-chain status. The US also has a self-interest in helping China develop its local economy, even at the cost of ceding some political ground to China’s growing regional influence. This policy of mutual accommodation has already been flagged by two of Biden’s foreign policy advisors:

“the goal should be, to establish favourable terms of coexistence with Beijing in four key competitive domains – military, economic, political and global governance.”

- Kurt M. Campbell and Jake Sullivan

The recognition, without explicit agreement, of the “One China” policy is one example, among many, of how differences between sovereign nations can be diplomatically accommodated. The mandate for this accommodation is trade. Such diplomatic nuance may be invaluable for both economies going forward.

Despite the occasional adversarial rhetoric, US banks and security investors remain welcome in China, which needs their expertise to help ensure efficient allocation of capital. China recognises that its own capital markets need to upgrade if it is to succeed in boosting domestic demand under the CCP’s “dual circulation” economic policy.

The new world unfolding will challenge the pre-conceived investment rules forged during the 2000s. Nutmeg’s fully managed, socially responsible investment and fixed allocation portfolios, will continue to be invested with a close eye on these changes. Likewise, our globally diversified multi-asset portfolios will continue to capture long-term returns delivered by new technology, while easing the volatility and risk of placing all your eggs in one geopolitical basket.

Risk warning

As with all investing, your capital is at risk. The value of your portfolio with Nutmeg can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you invest. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.